Phase 1: Early Days to Trondheim

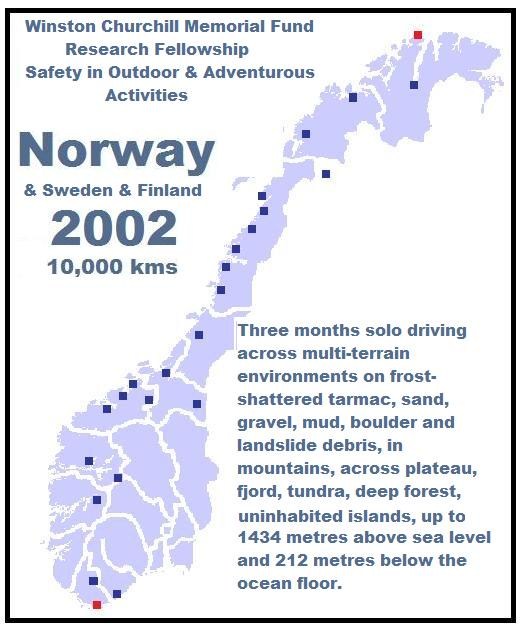

In the spring of 2002 I drove, solo, 10,000 kms through the length of Norway, to The North Cape, across to the Russian border, south through Finland and into Sweden, returning to the southernmost tip of Norway. The aim of this expedition was to visit outdoor pursuits centres, schools, county education authorities, private providers, and rescue services to ascertain the level of safety in placing young people in outdoor activities. The visit was the culmination of 14 months of planning and was made possible by a grant from The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust; I subsequently was awarded The Churchill Silver Medallion for the research. For those of you wondering why only silver – there is no gold! The following account contains diary entries, large extracts from the book written soon after I returned, and some of the 1,350 (film and digital) photographs taken. One of the aims of this website is to illustrate the logistics, strategy, team tactics, and drive, that were needed at the right time to make the solo venture a success. My background is education, mountaincraft, and combat survival. However due to or because of this I went into this 3 month journey realising that I had to be mentally tough as well as physically honed. I trained, and learnt – always learning – that without this, things can go pear-shaped quickly and you need a repertoire of experience, skills, and what the world may call ‘luck’ to get out of it.

The Journey, The Research, & The Solitude

[or 'the going, the doing, and the being']

"It seems strange to start writing the definitive account of all that’s been planned, executed, and researched whilst actually in Norway. My decision to begin now has been prompted by a number of events. One is that although with four days until I ferry back to the UK, I am staying in one of, if not the most famous of all mountain hotels or mountain stations in the whole of Norway – at Turtagrø. It seems fitting that a journey investigating safety in outdoor activities, especially mountaineering, should take place during The International Year of the Mountains, for me in Norway, Sweden, and Finland, just about to complete a 6,000 mile journey and surrounded here at Turtagrø by mountaineering history – started by British climbers. However I have no illusions about my contribution to this celebration of the use of the outdoors, mountain or otherwise. Certainly for me this expedition has been a massive undertaking, and yes, I have driven the equivalent from London to Kabul, all solo, but ‘small beer’ in the global scheme of things. I know others who’ve gone off for longer, made greater contributions, and changed government perceptions. But this is my contribution. Certainly I have tried over the past thirty years of outdoor work to ensure that the use of the outdoors develops, that we as adults have a responsibility to youth to impel them into outdoor activities, and that adult leaders get better at what they do. That is a three-fold mission statement formulated many years before ‘mission-statement’ were buzzwords.

So this research project has been, in a way, put into perspective. It’s a piece of the ‘development-of-the-use-of-the-outdoors’ jigsaw, albeit for me a large piece. However it is no more or less important than sitting down with my 15 yr.olds’ Year 10 Outdoor Education group and reviewing the way we did an activity – my delivery, their response, my expectations, their thoughts and feelings. What has to happen of course is that this Norwegian-Swedish-Finnish study has an impact on other things I do as a leader, on the team I work with, and subsequently on the clients we instruct, teach and educate." [Book]

"It is worthwhile to note here that another reason that I start writing the full account whilst still in Norway is that a tragedy has taken place in the Cumbrian fells in the past 24hrs. as I write this. A young boy, just 10 yrs. old has been swept to his death in a fast flowing stream in Glenridding. He was on a school visit. I am here in this country to look at their responses to off-site school trip safety and I have to comment, tomorrow, live on BBC radio, on the untimely death of this young boy, the ninth fatality on school journey party visits since January 2000." [ Diary]

Proper Preparation & Planning Prevents Pathetically Poor Performance

In my small green planning book for this expedition, the first few pages are nothing but lists of equipment for a 4x4, with its attendant costing – for this was always destined to be a journey. The research was to be the critical element but it wouldn’t take place without the journey that would get me from A to B to C.

I was going to work in amongst a variety of other challenging environments, coastal Arctic Norway – utterly remote, vidda (high plateau), Lapland with deep impenetrable taiga forest, driving up to 71º 10' north, high mountain over 1400 metres in winter conditions, plus being over 1000 kms north of the Arctic Circle. Temperatures were predicted to be down to -14º C and wind-speeds gusting to Force 10. This would give a windchill in excess of -40º C. Roads would vary from tarmac to oiled gravel to dust/gravel, from level to 1 in 2, from ruler straight, to 11 hairpins in 1700 metres distance climbing 900 metres. In places the snow was expected to be three metres deep. And I was on my own for the total duration. This was no place for a Ford Fiesta.

Of course the fuel had to be calculated. How far between petrol stations in Finnmark in late winter? Are these stations open on Sundays? What time do they open? When are Scandinavian Bank Holidays? How many mpg does a Frontera Mk.II do in relation to a Terrano 2.7 TD or a Defender Td5? Will I need jerrican back-up? Where? On a roof rack….?.....more wind resistance thus more fuel used. Inside? Will there be space? Gary and I threw all these calculations and a thousand more around for months, coming up with a definitive game plan four weeks before departure. 1200 man-hours of discussion took place.

What comes first-the route or the contacts? It sounds so easy now to answer that deceptively easy question. Do I go to schools, and outdoor education centres in a pattern, in an order….but I don’t and can’t choose when they might grant me an interview or a work placement. So what permutations are there? And what had to be considered in getting these permutations right….?....driving distance, timing, fuel consumption, fuel availability, energy – I was solo – road conditions, road works – snow, weather……..All these meant I had to sit down and design a route which would be a detailed plan of 6,000 miles – I actually worked in kilometres – with each being checked for access, cost (tunnels and bridges were going to cost me up to NKr 300 some days – NKr 3,600 if you include ferries) and sinuosity – was it cost or time effective to drive say 100 kms around fjord heads and over mountain passes to get just 25 kms. in a straight line for a ten minute interview? And can you judge the quality of an interview by the time it takes or its content?! Then a contingency had to be planned for that route because I might think the distance and time was worth it but half way along the route a ‘wild card’ appeared. A wild card was something I could not avoid but knew ‘it’ could happen at any time – I had to expect the unexpected eg. a landslide would block the road, or an unknown Bank Holiday meant I could not access kroner at the banks, or severe localised weather was against the predicted forecast. So every contingency had to be made to pay dividends, that is had to have built into it other interviews, contacts, or work placements or visits, otherwise I would or could lose three or four days research, or even be on the wrong side of the country when I needed to be somewhere else for a major interview.

Thus in 'Noddy-language', could I drive from say Kristiansand to Lilleström and then to Kinsarvik in x days ‘just’ to visit an exhibition? Would it be cost effective? ….not just with what technical information I’d get out of it but my energy factor, vehicle fuel consumption, and overnight costs. Can I drive all day, everyday? well of course not; and how far is a ‘reasonable distance’ if one is to drive before stopping for a rest? How busy are the roads? These then were serious questions to be answered – or attempts had to be made to answer them before the ‘off’ in mid April. Was even this the right time to start? And where to start? It seemed logical to start in the south and drive north, chasing the winter as it retreated the 2000 mile length of the country. Could I link up outdoor centres, county education authorities, rescue teams, with a feasible route? with their opening times – much of Scandinavia may be closed this end of the year, and too busy later in the year. Winter lingers on into June in the Jotunheim, Jostedalsbre, Setesdalen, Hemsdalen, Dovrefjell, Abisko, and a few other places. The British have zero concepts about roads closed for winter. I would have to time the journey just right – leave too late or drive too slow and quite simply I’d not arrive in Vadsø my most north-easterly visit; leave too early or drive too far and fast and I’d overtake winter and get stuck anyway – or at least everywhere would be closed. Gary and I worked in, on, and around the Land Rover, once it arrived, constantly building this kit into the vehicle, to all intents and purposes fitting it like a three-dimensional jigsaw. Even so, after all this meticulous preparation I still honed it even more when I arrived in Kinsarvik, my Advanced Base. Two boxes of gear never travelled on with me. One of my criteria was to have only enough kit to enable me to survive well and that it should not, when packed in the back of the wagon, come higher than my eye level looking in the rear view mirror.

Gary then controlled all the kit. He did a perfect job – suggesting, acquiring, adapting, and inventing – always ready to chuck out his ideas if mine were fixed and uncompromising. It happened that out of the 800 or so items of kit I carried, only a dozen or so were thrown out – a tribute to this man’s insight into Quartermastering. While all this was happening in twice-weekly, 20 hrs per week packing sessions, the ‘Legal Desk’ was opened. All the paperwork pertaining to the smooth running of the expedition had to be squared away but just to illustrate how things could easily slip if I wasn’t on top of them: I’d booked the ferry with the local travel agent in Leigh, retaining all the paperwork issued. After three weeks I checked with their office as I had not heard anything by way of confirmation. I was told that the staff member who I’d seen (and who I used to teach) had not booked with DFDS. I had no ferry. Needless to say butts were kicked. I delegated none of the paperwork on the ‘Legal Desk’. I had to have a handle on every aspect of regulations, ferry conditions, research permits, currency – I carried NKr 36,000 in cash alone – motoring law for each country, Customs Manifests, insurances – I had four of these – etc. etc.

The fact that Gary was managing the kit left me free at times to sort the paper: the Customs Manifest was four pages of close-typed A4. For a lone driver travelling an unorthodox route, across mountain borders I had to produce legitimate evidence of why I was carrying certain items. Bearing in mind the importance of the research and the journey linking sites, a comprehensive set of records was planned. Now, hands-up all those of you who with good intentions start keeping records, only to miss key events, data, and information rendering the record useless? We’ve all done it. But here, solo, there was no room for a slovenly approach to recording interviews, day-to-day events, vehicle data, images, and route. After all if I didn’t do it no-one else would.

How one person could do all this, and drive 6,000 miles, plan-execute on a daily basis all the interviews ie. set them up in situ, and after write up detail, write up the daily diary, do all the domestic things – washing clothes, eating, maintaining the vehicle, plan the route (a singularly huge undertaking on its own) and then drive it, navigating – and still find some time to relax is a very tall order. I never had more than 45 minutes clear relaxation time on any one evening, unless I stayed awake into the early hours – which was counter-productive in itself. So how was I to handle the record keeping? A video diary was planned – and taking two video cameras made life a bit more manageable; so a large amount of video footage, documentary style in some cases, to illustrate environments. I took about 1000 still photos on 35 mm format using two Olympus cameras one with a 150 mm zoom, and a Leica-lensed Minolta. One camera was in my pocket for the duration of the exped. – never knowing when you’ll need instant access.

The vehicle record was to be, in reality, the route record produced on a daily or part-daily basis. This included fuel taken on-board, weather conditions, and environment. I’ve seen a simpler form of this record used before on The Oxford and Cambridge Far Eastern Expedition and I’ve always maintained that it’s the real ‘guts’ of all the records. I always look to see if overland expeditions include a route record – it says a lot. All these things were planned, but in the final scheme of things literally, would I have a) time, b) the self discipline to carry them out? After all when you are snug in your warm 4x4 in the middle of the Swedish Lapp tundra with a blizzard screaming horizontally across the front of the Land Rover, do you really want to stop, get out and set up the camera? I know (now) that it’s easy to create a dozen reasons why one shouldn’t stop and get out; but quite simply, if you don’t get it done you’ll lose the moment and probably regret it.

Gary and I broke all the kit down into a Domestic Box carrying everything from bin liners to boot polish, and washing powder to water; an Office Box contained eg. stationery, school brochures, paper, envelopes, questionnaires, letters of introduction, and books; a Food Box – self sufficient for 20 days, including tinned food, ration packs, and all the paraphernalia for cooking – stoves. A Survival Box had kit that was not ‘sac-portable’ but would aid vehicle based survival should things go pear-shaped: Volcano Kettle (one of the best and most unsung inventions for outdoor work in the last 150 years), tinder, kindling, crampons, collapsible bucket, ice-axes, helmet, ice-screws, lamps etc..

The book's Appendices list everything. I was and had to be prepared for every eventuality; being literally self-sufficient, prepared for anything, was designed to give me peace of mind. It was to be one of the key factors in my ‘zero-worry’ approach once on the road for eight weeks. Should everything go nasty on me I had the practised capability to survive in a wilderness environment for at least three weeks, and possibly indefinitely. It was a remarkably comforting feeling. But I wasn’t planning to have an emergency survival situation. No-one ever does.

A major factor in the planning was the Home Team. Gary and Sean volunteered to be my ‘administrative tail’ – fully conversant with everything I was planning to do, fully prepared to accommodate a change in this plan and having a management capability to launch an emergency search, recovery, or rescue plan from their UK base in liaison with the Norwegian authorities. They each had copies of all legal documents, my contacts, etas., proposed routes, and my in-field set-contingencies. In addition Gary would monitor my route progress on a day-to-three-day basis, that is he’s not planning to worry if he’s not hearing from me for up to three days – with a sliding scale of pre-planned contingencies should the situation escalate. This set-up worked perfectly. Usually Gary and I would carve out every Thursday afternoon, for seven months, and throw ideas around, create ‘what-if-scenarios’, and generate best-kit options – not necessarily the most expensive kit but the best. This was all conducted in what I termed a Situations Clinic.

We both knew that the potential for crises was potentially huge, once I was on the road. However with the best kit, the best vehicle, thirty years of experience – much of it in Scandinavia – good planning, useful contacts, a well informed and experienced Home Team, and as far as could be achieved this end, training, the risk of these crises occurring would be minimised, and the chance of them escalating out of control kept to a managed minimum. Sometimes on those Thursdays we’d get to the point where we’d just race off to BJ Camping in Rayleigh or C&G on Canvey, or elsewhere, bending their ear about this bit of kit or that item of clothing, possibly sourcing the most unusual items from obscure and bizarre places. The Volcano Kettle was a prime example. I knew its reputation – but where to get one? No-one locally had even hear of one let alone used one on an expedition. Gary – who else?! - sourced one through the internet, and, as was expected long ago, it found its way straight into my Top Ten Kit list. It had of course to be trialled first. A solo venture where kit fails means not only that it’s an embuggerence when it happens, but the now useless item uses up load space, is dangerous if you depend on it, and your time and effort are wasted.

I planned to ice climb, mountain walk, backpack in forest, backpack across mountain, and up-grade wilderness skills, in addition to the interview-research and driving modes. Thus the range of technical equipment I wanted to take would be vast. Four sacs, three pairs of boots, two ice axes, an axe, supplemented by another in Sweden – home of the famous Gränsfors – a golok, a Seal Pup my constant-companion-survival-knife, a mountain tent, a Gore-Tex bivvi tent, plus a basha permutation linked to the Land Rover that we invented for vehicle-based woodland and forest work. Thermal base-layers, mid, fleece layer, and shell Gore-Tex mountain jacket, and a Gore-Tex ‘forest’ jacket. Full ‘green’ kit of double lined DPM winter trousers, thermal layer and HH fleece, four litres of fuel for two stoves, the latter stored in, for immediate purposed, my German winter sac….it goes without saying that added to this for even a day walk was a set of two stills cameras, a Sony digital video camera….I did and always do try to keep a light sac!

I had five medical kits, all of different permutations; the last thing I wanted was to sort out big, small, vehicle, and ‘sac, types of med. kits every time I trekked off somewhere: a large trauma kit mainly for RTA type emergencies, a Mountain Leaders med. kit with additions in my mountain sac, a smaller one in my green sac. A back-up medical bag was in the front of the Land Rover, with an identical one taped inside the rear off-side window. I had made up my own suture kit from modified fish hooks of various sizes and the finest catgut – to able to be used one-handed. My SAK pliers would double as the forceps/pliers here. No anaesthetic – only to be used in dire personal need. This then is just a snapshot of the equipment. If it makes for laborious reading, I make no apologies – there was a lot more. The original date of 22nd April 2002 was brought forward by a week for logistical and strategic reasons. I had one more task waiting me – a kilometre by kilometre route plan prepared on paper. However without being superstitious, which I am not in the slightest, I decided to postpone this task until I had officially been awarded the 2002 Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Travelling Research Fellowship.

Beating thousands it was a good feeling to be successful. I was awarded the Fellowship, and could get even more stuck into the preparations – if that was possible. Day to day running of the Outdoor Education Team and all the events, practicals, and off-site courses took second place to things-expeditional. Ten of my closest friends and/or those who’d expressed genuine interest in the exped. kindly gave me ‘practical’ encouragement. You know who you are and your contributions will be made plain throughout the course of the journey and its research. Needless to say all that you guys gave me kept me going. I had a day’s ‘Council of War’ with Gary and Sean – my Home Team - to talk through every element of the duration of being in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. With Gary’s encyclopædic knowledge of both the nuts-and-bolts of the kit as well as a thorough familiarity with the way that I think, plus Sean’s analytical mind and exemplary total commitment to any Team task we’re involved in, these guys listened and fired questions. A healthy time. With impeccable timing, the BBC decided they’d like to do a live radio interview with me on the same day as the meet with the Home Team; the guys could listen and tape it. Things-BBC were set for quite a dramatic conclusion. Watch this space.

As weeks before departure turned into days I was found by all the KJ staff to be wandering the corridors almost like a lost soul at times – my mind was elsewhere. Annie and Jo, Craig and Sharon, and all the others were asking how ‘it’ was going, and all I could say was that I wanted to be there as soon as possible! ‘There’ of course being on the ground in Norway and getting the work done. The waiting was getting to me just a bit. Psyching yourself up for being solo for three months is not something that you can do in a day. It was a singularly unreal time. Leaving a staff, 120 of them, to try to manage lunch-hour discipline on their own, leaving Jan to manage her Mum without at least a presence from me, leaving Sam, Meg, and Beth which for every reason was gut-wrenchingly upsetting. All this was so very hard. Leaving the care of those closest friends at work, and The Team with whom one develops such closeness in the white-heat of the stress and pressure that is the job. Leaving them was very, very hard. I was going to miss the glimpses of great friends who just catch your eye long enough to say ‘Hi, yes, I’m ok, but this stress is not the real world, is it?!!’

(ABOVE) Day 1......up at the start'ish of Setesdalen by the Otra having lunch .... in what was to become a familiar pattern of bread/cheeses/ham/fruit/choc.

The 'Off'

At dawn on a quiet and sunny April morning, the Td5, already affectionately known as 'Winston' for obvious reasons, slipped his moorings and motored north up the Great North Road heading for Tyne Commission Quay in Newcastle. He had just 800 miles on the clock - it would be reading some 7,000 by the time I made it back home. This was some vehicle. Retford was an important stopping-off point on the journey since I lived there for five years in the 70's and can re-victual there without deviating from the route too much. Rather surreal walking around getting last-minute bits; but none-the-less good to be on the road at last. I had the very best equipment in the world including the definitive overland expedition vehicle, 30 years experience of outdoor work from the high-Arctic to the Carpathians, from the Alps to Scottish winters. My team was the best. The budget extensive. No reason at all then why this shouldn't go swimmingly. Got to Tyne Commission without any fuss and spent a good hour in the queue being stared at by the grockles who would no doubt accompany me sailing north. A few expedition vehicles turned up with kayaks. Checking in whilst sitting in the vehicle, the clerk was asking lots of questions - not about the journey but the Land Rover; another portent of things to come. The ferry journey was straightforward and pleasant. Such is modern communications, my next door neighbour, Pete, was in a meeting in a building high up on the hill overlooking the Tyne down which we slowly sailed. Before I'd got out of the river he'd taken a picture of the ship with his digital camera, dowloaded it to Babs his wife who'd printed it off and handed it to Jan, virtually in real time. I was actually on that side of the ship as we sailed out. An SAR Nimrod flew overhead on an exercise when we were some way out to sea, which in the event was a bizarre portent of things to come. I went off to read the first part of Sean's journal of Africa.

What to make of my first task once disembarking in Kristiansand was concerning me. Jeremy, my nephew has a Norwegian girlfriend (since married); they live in the UK; her sister Vanessa lives in Kristiansand where I am about to dock. Her faxed map of how to get to her house has no name or number. So, this should be interesting driving around a strange town, looking for someone I have no description of at an address I also do not know. But first to the Customs Hall where I had to collect my impounded survival knives. As in all overland journies it's always the built-up areas that bugger-up your nav.. New town, different driving side - I'm later than planned - and there's me driving up and down, up and down Kongsalle on the attractive east side. Eventually this bright, vivacious blonde with an impish sense of humour, a penchant for dark glasses and 'classic' Scandinavian dress style came strolling over to the car park, co-incidentally right opposite her house. There was an immediate warmth about her, and she really did treat me as family. (She did literally become family three years later when she married my other nephew, Jeremy's brother Dan). Vanessa Berger was my first and only passenger on the whole of the 6,000 miles travelled in the three countries. She had to go into Lillesand that afternoon for a dentist appointment, some 20 k's down the road. En route she introduced me to the Head of Physical Ed. at her College. Eric gave up his free lesson to chat to me. The start then of some valuable research.

Lillesand was a magical place, and arguably one of the most beautiful in Norway. I know that is quite a claim, but actually having been to most of the supposed beautiful locations in the country I reckon I am particularly well qualified to judge. Lillesand in Spring assaulted the senses, especially as I was sitting by a table at a coffee bar on railed decking at the harbour's edge, with the sun streaming down and creating glare from the all-white painted clapper-board buildings here. I was due to meet Vanessa in half an hour, so time for reflection.

(ABOVE: Lillesand) These thoughts turned to other overlanders as I sat in the warm surroundings of this idyllic large village. I had read-up on as many accounts of solo overlanders as I could but the library on solo drives - especially in cold climates - was painfully (and worryingly) thin. What I still needed even at this late stage was to see how individuals had tackled all the driving, nav'ing whilst on the move, fuel economy, and solitude. As there was no pool of published experience I'd have to create my own systems en-route.

Vanessa and boy-friend Klas made a great fuss of me with their relaxed hospitality. I had to stay a second night as I received an e-mail from the Asst. Direktor of Education for Vest-Agder County (in which I was staying) inviting me to discuss my research with her - one Kari Skogen. She was most helpful. I stayed in her office for a good couple of hours, trawling through statistics and government proposals.

Asked if I'd like to visit a primary school to see outdoor education in action I jumped at the chance. Thus I landed up at the Ovre Slettheia Skole with teachers Nina and Matias plus 27 Grade 3s. The headteacher was Gerdlinger Haugland.

Thus started the first hands-on research. Walking into a foreign school, where pupils look quizically at this foreigner, is a daunting expereince. But one which was to become second nature to me by the end of the exped.. Knowing full well that I'm disturbing the teachers' format for the day (and was the Headteacher happy for me to be there?) tends to make for potentially icy introductions.

I had no reason to worry. This stunning blonde was standing by the main entrance to the building. "Hi! You must be Barry Howard the Englishman!" she said with a big smile. And it turned out Nina was the class teacher; dressed in a one-piece black winter ski-suit, she stated that in 15 mins the class were out for thr rest of the day doing some activities. First however I was introduced to all the staff in the staffroom, offered lunch and tea, and met Matias the male other half of the staff duo running this class. All the pupils bar two were ethnic minorities they said so communication is unusual.

I had a wonderful time - with wonderful pupils. They were friendly and inquisitive as only children could be. They giggled and stared at me. They tried to speak some English, I replied in faltering Norwegian which had them rolling around laughing. One took me by the hand and with Nina showed me the very large classroom which was their base. It was actually two classrooms knocked into one - a cabin/hut separate from the main building on this forested campus high up on the top of the hill overlooking Kristiansand.

My hut at the school where I worked was more closely related to the garden-shed branch of hut ancestry than this triple glazed, quality, heated, foyered, and roomy building; it being a direct descendant of the Scandinavinan mountain cabin branch of the hut family-tree. Of course there was no jealously here!

We walked for ten minutes. I was in the company of Matias an ex-regular military guy who'd given it all up to come into teaching. As we talked en-route along 200m or so of steep rocky woodland, virtually none of the 27 pupils stayed with us, they just evaporated into the ever thickening woodland. At one point I turned around hearing squeaky young voices to my right and slightly behind, only to glimpse three boys some eight to ten metres up a crag wondering how to get down.

I couldn't stay at Ovre Slettheia until late in the day as I had prep to do for the departure tomorrow. So catching a bus down into town I planned to re-sort the contents of Winston using the large empty car park in Kongsalle. The rear load compartment was full to over-eye level if I looked in the rear view mirror - jackets, sleeping bag, kippmat, and an overnight sac all lived on the top of the packed kit. However for daily use the whole of the passenger compartment (photo above left), footwell and seat contained at arm's length everything I needed: a set of five maps at 1:335,000 or 1:400,000 scale produced by Cappelens - simply the best. These of course had to be pre-folded so to ease my hour-to-hour navigation. You can't open a Cappelens in the cab of a Land Rover - or any other vehicle for that matter - whether you are static or, even more daft, on the move. Kart 4 for example is almost two metres tall.

Solo driving is one thing, solo navigating is another, and map appreciation, map preparation, and route building are yet another - all totally different. I planned rigorously each stage of the following day's route - every evening - and committed the whole lot to memory. I built in contingencies for each day to take account of possible landlsides (I encountered 13, two of which I came close to being hit by), avalanches, road accidents (two in three months of driving) winter snow (narrowly missed by days). The effort paid off.

In addition to the map box in the front I had research papers, guide books, a library of Lonely Planet Guides, flasks clipped to the dashboard: hot and cold waters, one very large first aid kit used to great effect later in the exped, a camera at the ready on timed and/or automatic mounted sometimes on the very usefully wide flat dashboad top of the Defender (takes cups too!), audio tapes and CDs, video cameras, a huge box of sweets, and one of the most important bits of 'logs' my NavLog completed religiously every day. Eight years later I would still be using it as a major resource in expedition planning.

One piece of kit was potentially a life saver: the Americans called it a Bug-Out-Bag, I call it a Grab Bag; whatever, it complimented all those bits described above but with the additional advantage that I could survive a major loss of assets (eg vehicle and/or monies) and mount a safe return without say the vehicle should fire, crash, or other Act of God render me stranded. I carried passport, all currency, vehicle docs, driving licence, various carnets on me at all times (I wore a modified form of what we call an 'assault vest' like a simple form of anglers gilet with a lot of pockets), but in the Grab Bag was food, waterproof jacket, used video camera tapes, radio, embassy details throughout Scandinavia, phone, all insurances, second torch/batteries, accommodation details for pan-Scandinavia, 8 km strobe, travellers cheques up £3,000, and one change of clothes.

It was a functioning system that survived 10,000 kms of journeying.

I drove out of Kristiansand into heavy early morning traffic but soon lost all the car-borne commuters once westbound heading for Lindesnes. I love this road; it always makes me smile, once beyond the last slip road near the cutting on Route E39...you look in your rear-view mirror and....no traffic; it's a very quiet road. But then they all are.

No-one in Norway drives the length of the country; why would they? But here I was at Lindesnes the most southerly point of the mainland of Norway; parked up just to be there and turned the Land Rover round and maybe, just maybe get to the North Cape one day on this exped; it would be a very 'complete' thing to do and add a bit of fun to say I'd driven the length of Norway - all 2,400'ish road miles. It rained heavily as if to say "....don't hang around here - get back on the road!" I did and it stopped raining, the sun accompanying me on a beautiful, and smooth, drive up through the valleys through Vage, Vigmostad, and Viblemo. This was Route 460, pastoral and hilly, not really mountainous, with locals' eyes giving me what was to become a regular long 'stare'. 123 miles after leaving Lindesnes I pulled up in the quiet village of Evje. Time to shop. It was only 11am.

After a bit of a shock at the prices in the grocery store I drive the short distance down to an outdoor centre (TrollActiv AS: photo: below left) I'd arranged to visit run by a Brit, one Tim Davis; he was out but I had a good chat to his secretary, getting some very useful info. Nice place which will repay a visit. As a team got ready for a rafting session, the participants standing by the tan-coloured buildings in the gravel car park - eyes averting to watch me climb up into the cab, fire-up and drive off I realised that this vehicle turns heads. Regardless of that, I was hungry. Time for a brew too - by the stunning Otra River just off Route 9 in a lay-by alongside Syrveitfossen.

I decided on pushing through to Kinsarvik. This was quite a decision as I'd already driven 232 miles today and I knew there was some serious high level driving up ahead at the top of Hovden; but I went for it and did not regret the 1,300 metres asl roads, snow, brilliant sunshine, and airy 1 in 3 descents, all the while listening to Whitney Houston on the radio, at an average descent of 1 in 7 ....for 10kms. I arrived in Kinsarvik on Hardanger at 7pm to a great, warm, almost family welcome from my friends Dag, and Nils Instanes. It was so good to be back - certainly my second home in Norway. Below: Nils Instanes' centre.

The time at Hardangertun was one of 'admin' - those of you who've been on long range expeds know that preparation is the key, so checking med kits, full check of Winston's working parts, re-packing sacs, and memorising routes, and not least of which resting as it had been a very, very, busy lead up to departing the UK. The amount of kit I had was huge - too much packed by Gary in fact but here at 'ABC' better to have too much than too little, so I stored a couple of very large boxes of kit here. Otherwise it was use the facilities of the cabin - power to charge cameras etc, check the weather forecast, find which passes were open after the winter.... once I'd repacked the three dimensional jigsaw in Winston's load compartment.

Thinking of the Home Team, and getting up at dawn...a simple breakfast and the overnight bag slotted into it's place behind the passeger seat - where it would be for the next two or three months - and I quietly motored through the Centre, out of the gates and left onto the characteristically smooth tarmac - now heading to go up through the Eidfjord gorges, through Mabodalen but not before paying a brief visit to one of my favourite places in southern Norway: the Nature Centre in Ovre Eidfjord. Then up onto the Hardangervidda.

This is a spectcaular place and I'd been catapaulted staright back into winter once Winston had levelled out onto the vast plateau.

ABOVE: The Hardangervidda looking east north east; I'd hit winter, with temperatures down to about -6 deg C and windchill much lower; the road had been open about two days.....good driving conditions? Well, what do you think?!!!

" I was not too sure how far I'd get today; the aim for this stage was Jostedals, somewhere in or on the periphery of the ice cap; and this journey over the 'vidda was an exploratory aim, so I'm driving across it to get to Gol and Geilo, dog-legging as it were, east then north west" (Diary extract 19 April 2002)

I went up Hemsedalen and Morkedalen - all sort of like Setesdalen but on steroids - and reaching some airy altitudes eg around 1140 metres above sea level on the the road, all accompanied by some outrageous serpentine bends. These I came to be quite accomplished at negotiating - but nevertheless still a bit hairy when you are on your own - descending - on the 'other' side of the road, and then having to reverse to allow up-coming approaching traffic. Meet an articulated lorry on a hairpin, where, on the serious mountain-sides, the gradient is 1 in 2, you were (and I was) duty bound undertake one or more of these reverses up and around the bend which you'd just driven, on a vertical cliff top - a bit gripping if the cliff edge is the side where your passenger would normally sit ie you can't see the edge... and I had no passenger. Shut off the radio, listen to the revs, know your own vehicle : length and width, and concentrate. Don't breathe a sigh of relief when you've got through it because if you are driving the length of Norway - and I was - there were going to be anothe 87 of these hairpins along the route; one series in particular was to take me 900 m up in just 1,700 m distance. I'll leave you to work out the gradient.

I got down to Borlaug Youth Hostel; virtually empty, and a very cold night with equally very deep frost the next morning at the 8am 'off', but stunning views in Laerdal and down to Sognefjord, which as every school geography pupil should know is the longest fjord in Norway at 127 miles. I kept stopping to take video and still photos but had to 'discipline' myself not to forever park up in Winston to take happy snaps as I'd never get the 2,649 miles to North Cape, let alone visit all the Education Dept. offices, schools, and outdoor centres. This was not a jolly.

In this place of superlatives I was crossing the Fodnes-Mannheller ferry in brilliant sunshine but avoiding for now the Laerdalstunnelen (BELOW), the world's longest road tunnel at 15.23 miles. I will look forward to driving through this on my return here in some eight or nine weeks time.

I had planned to visit the Jostedalsbree Nasjonalparksenter 'up the road'. Well 40 kms from my overnight stay at Mindresunde, but despite agreeing a meet date and time - it was closed. This was a familiar pattern I was to encounter week after week - too late for winter opening and too early for summer. April seems to be a non-entity in Norway - nothing opening until at the earliest 1st May, usually 15th May, and north of 66 deg. 1st June. My policy of collecting any information in brochure form with even the slightest relevance to the research wherever I am, paid off. I was reading through a leaflet on 'Briksdal Glacier Guiding'. This was a company I'd heard about in the UK and I wanted to interview them. First a quick drive into Stryn and a phone call, and it was booked, an interview in an hour's time at The Briksdal Centre, 41 klicks south of Olderdalen, then into Briksdalen, right in the heart of the ice caps, as deep as you can drive into Jostedalsbreen.

I landed up spending an afternoon with Frodo Briksdal a fifth-generation mountain guide, drinking his coffee and absorbing his views on leadership, guiding, and outdoor pursuits in the commercial world. All music to my ears. We managed to get up onto Briksdalsbreen and also under the glacier - 25 minutes trekking under half a million tonnes of (moving) ice cracking reports like gunshot does tend to concentrate the mind wonderfully!

I eventually landed up in Alesund in a long, heavy, downpour - though not wanting to stay in the town despite it being a really attractive one; I'd always preferred to be out in the sticks, holed up in some cabin or remote camp but the terrain was pretty unsuitable thus here I was in a hotel. One of only three of the whole exped.. With skip loads of admin to do, and needing to do some washing and booking some flights this seemed to tick all the boxes. Besides, the Receptionist was a very nice lass who seemed pleased to help direct me to the right places in town - and the hotel's laundry.

Apart from watching the Royal Norwegian Navy test some Merlins on an amphibious docking assault ship in the harbour, I dashed all over the place to get interviews written up, recorded, booked, along with a abortive visits to a flight broker to book a seat on a Wideroes Dash 8 to Oslo; to no avail....and so acted as my own broker in the end by haggling in a sort of Henry Kissinger Shuttle-Diplomacy playing one company off against another. Which to my surprise worked - tempered only by the fact that when I got back to Winston I had a parking ticket for being one minute over time; that cost me NKr 300. I tracked down a Parking Attendant - asked where to pay and then checked out of the hotel and made my way to Molde. This was probably not my best move as the accommodation - booked ahead by the Tourist Info Office in the town - proved to be no more than a 3m x 2.5m tiny (understatement) cabin with no water, no provision of disposing of water, no crockery, no pots/pans, no cutlery, but, bizarrely a cooker. Brassed off, I made my feeling known to my video diary and merely 'camped' in the cabin, for there was not a scrap of luxury. Fortunately I carried my own pots, pans, crockery, fuel, water, food, wash-up facilities, and so managed - and managed well, but resented paying what amounted to over £30 for a shell of a hut.

Liv Marie Opstad's valient efforts to secure interviews then a work placement in More og Romsdal came to nought through no fault of her own; but it left me high and dry in Molde. I elected to leave during a stormy early morning, to drive the famous Atlanterhavsveien. This routeway had been built out to sea linking 17 islands. Every adjective in the book had been used to describe this amazing but typically understated feat of Norwegian engineering. I had to drive it. However as it was pouring with rain and blowing a gale it was sure to be an 'interesting' drive. I'm by now beginning to think that I 'wrote the book' on 'interesting'.

" A Land Rover Defender is the least aerodynamic vehicle made - it is slab-sided, more akin to a removals lorry than a car, and is the only vehicle with flat-glass windows; there are no curves of any consequence on a Defender. So with a powerful engine propelling this two tonnes of steel and aluminium with all the ballistic and aerodynamic qualities of a house brick, I drove on to the Atlanterhavsveien. It fulfilled my every expectation. Eight kilometres of gale-lashed road at sea level, with water both sides of the road, spray peppering the Land Rover, and no traffic, solo-driving, all again, concentrating the mind wonderfully. There are eight bridges along the 8.27 kms., one of which, the Storseisundetbrua, is 260m long but rises 23 metres at an 8% gradient. From some angles it really does look as if I was going to fall off the end. See photo.

I drove into Kristiansund feeling more relaxed than at any time on the whole exped. I'd been on the road in Norway a week, and I guess the routine had now been established of living - driving, o/nights, cooking en-route, exploring, interviewing in and on my own mobile-activity-platform ie the Land Rover. Quite simply it worked. Loneliness is not a factor here, and in the midday sun out beyond 'Sund, wonder why; probably good contact with the Home Team, and the various packages I'd been given by folks at work and on the Team - Trev, Tony & Lorraine, Annie, Tim, Sean, Kat, and others, all opened at different stages along the 6,000 miles being full of fun, advice (I use that word very loosely!), meaningless good humour, music, Scotch (most welcome...thanks Sharon), letters, posters, pin-ups, and even an Action Man dressed in a KJ T-shirt. All very important in maintaining links - and a psychological balance. For working solo for a day or two is one thing, a week is entirely different and by then you'd know whether it's all going to 'work' for you....by a month you would already have gone barking mad. After over two months I'd felt as if I'd just started.

The contender for BJH's 'Trans-Scan Best Cabin Award' arrived in the form of a Centre in Orkanger - the exact opposite of the night before in Molde for just a few kroner more. Pity I was only staying a night. Sumputuous almost; having bought a bag-full of sticky buns in the bakery 20 klicks back the first thing I did (of course) was get a brew on and dive into the stickiness. That tasted real good.

I did an assessment of what feels, strategically, to be the end of 'Phase 1' of the exped.. Everything seemed shipshape and squared away; keeping an eye on money was important. Norway's expensive - but manageable - and if you 'cut your cloth' accordingly it's feasible to live comfortably, drive, and eat on a long range foray. Just remember to dovetail in the work where you can and rest up frequently rather than go hell-for-leather along the forever-quiet roads (which make one think that one can just drive, drive, drive all day....dangerous). At first I felt a bit guilty about stopping on perfectly good roads, in perfectly good weather, with traffic at two cars per hour. I soon learnt that frequent'ish stops (every couple of hours) are necessary; burn-out mode can hit you when you least expect it - and you can bet then the local trolls and djinns will have timed their appearance in the form of a precipice drive, landslide across your road, or severe weather just as you are at the end of a stupid 600 klicks drive in one day....'just because you can'. Take my advice. Don't.

Phone: 07940 701468

Email: huntertraining@hotmail.com